After years of reviewing aluminium profile designs, we’ve seen the same issues come back again and again. None of these are “rookie mistakes,” but rather logical assumptions that simply don’t hold up once aluminium starts flowing through a die under hundreds (or thousands) of tonnes of pressure.

Below is a breakdown of the most common extrusion mistakes we see, and we fix them. For more in-depth details, you can check out our guide to designing bespoke aluminium profiles.

1. Assuming “if it can handle more, it can handle less”

In extrusion, this logic is backwards.

A large press does not automatically work for small or delicate profiles. For example, pushing 1,800–2,000 tonnes of force through a profile with a circumscribed diameter of around 45 mm is asking for problems, especially when sections of the profile drop to 1 mm thickness.

You cannot force very high pressure through thin sections without distortion. If the profile geometry demands high pressure, the diameter must increase or the shape must be adapted. Otherwise, the profile will bend, twist, or exit the die unevenly.

Press size must match the circumscribed diameter and wall thickness, not just the overall profile size.

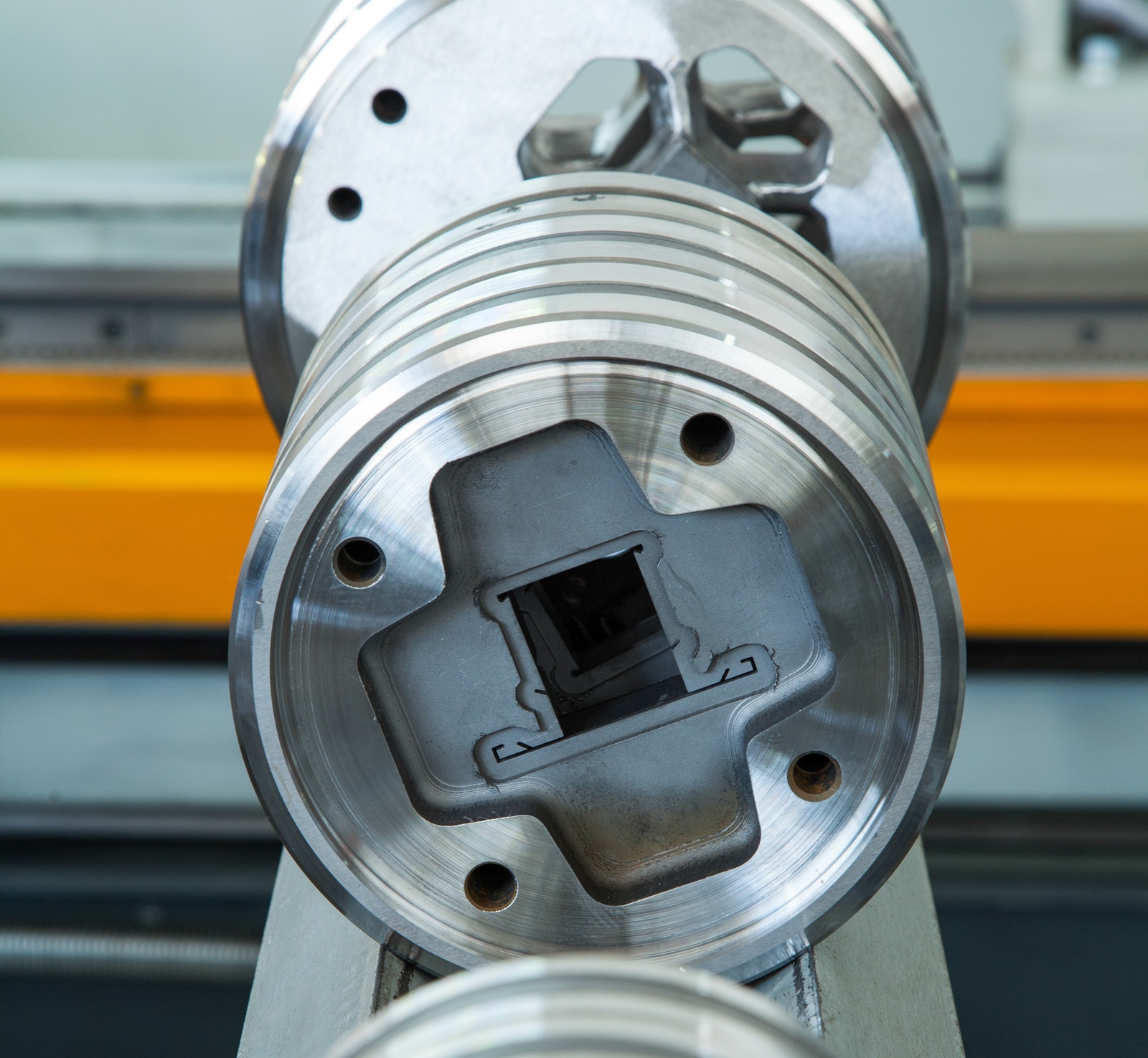

2. Ignoring die support and “push zones”

Aluminium does not flow evenly by default. Each part of a profile is pushed differently depending on local wall thickness, distance from die support, and bearing resistance.

If the profile is not designed around how it is pushed against the die, aluminium will accelerate in some areas and lag in others. The result is warping, bowing, or tolerance drift.

In difficult cases, extruders may need to adjust alloy chemistry to stabilise flow. This is sometimes necessary, but it is not ideal and it is often avoidable with better upstream design.

3. Too many exits (multi-exit = multi-problems)

Multiple exits on a die sound efficient, but in practice they multiply flow imbalance, tolerance variation, and correction time.

At ALUCAD, we always prioritise single-exit dies, which should be the case whenever precision matters because they allow better flow control and more predictable tolerances.

Throughput may be lower, but scrap rates, die corrections, and quality-control complexity drop significantly.

4. Poor cantilever length design

This is one of the biggest and least understood issues with extrusion.

Cantilever length directly affects how aluminium flows through the die. Too long and section cool and slow unevenly. Too short and the aluminium accelerates uncontrollably.

We frequently recommend design modifications to adjust cantilever lengths in order to stabilise flow, prevent exit-side bending, and improve dimensional repeatability.

5. Lack of symmetry (or unbalanced thickness)

Perfect symmetry is not always possible. Balanced flow, however, is non-negotiable.

When one quadrant of a profile offers more resistance than another, aluminium naturally flows faster elsewhere. That’s when profiles twist and tolerances drift. To adjust symmetry, fixes often include increasing thickness in low-resistance zones or reducing thickness where flow is too fast.

Even small changes can significantly improve tolerance stability.

6. Over-specifying tolerances for no functional reason

We regularly see aerospace-level tolerances specified for profiles used in building and construction components. This is expensive, and unnecessary.

In most cases, ultra-tight tolerances do not improve performance. What they do cause is slower extrusion speeds, more die corrections, longer quality control, and much higher rejection rates.

All of this increases costs, sometimes doubling or even tripling them, with no functional benefit. Unless the application genuinely demands it, looser (but controlled) tolerances are the smarter choice.

7. Designing solid profiles when hollows do the job

This is less a mistake and more a question of optimisation. If a profile is fully solid, we always review if it needs to be.

Introducing hollows reduces unnecessary material usage, lowers weight, and improves handling, lowering overall costs (tooling cost does not increase when supplied through ALUCAD) without affecting the product’s mechanical requirements. In most cases, hollows are a win.

8. Long flat surfaces and surface finish surprises

Long flat surfaces are risky. Extrusion lines become visible, and cooling variations can show up later.

To manage this, add decorative elements such as ribs or ripples, but if absolute flatness is required, anodising can help, though it introduces another issue.

During anodisation, thickness differences become visible due to uneven reaction, making some areas appear slightly whiter or darker. The best solution is to polish before anodising. This nearly masks the issue completely.

If you’re designing a bespoke extruded aluminium product and want to get the most out of it technically, functionally, and economically, send us your profile drawings and technical requirements.

We’ll review the design, challenge it where needed, and provide a cost-effective quotation. Get in touch.

Follow us on LinkedIn to stay updated with our aluminium profile manufacturing insights.